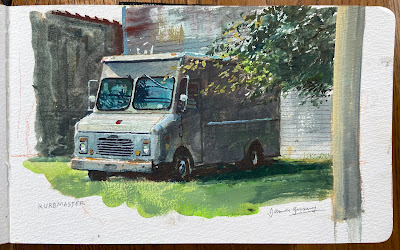

A reader asked: “How is your thought process different at the beginning of a plein-air painting compared to the end?”

At the beginning of a painting, I think about the concept or feeling that I want to convey. That intention guides the choice of framing and the colors I may choose. The thought process always comes before the painting, and if it’s a studio illustration, I work it out in sketches.

If I were to start drawing or painting without a clear idea, it’s likely to be a dud.

My first goal is to make a foundation in simple lines drawn with a brush, graphite pencil or watercolor pencil. If my goal is to capture the subject fairly literally or accurately, I might do some measuring and checking. Other times I may just use the elements in front of me to build an idea that’s half formed in my head.

Either way, my goal at the outset is to place the big elements.

There may be moments of struggle, especially in the early stages when trying to align the actual painting with the original vision in my head. To overcome this, I often focus on finishing one area and building from there.

As I progress towards the later stages of the painting, my focus shifts into the scene. I think about the details. If the painting is going well, my attention shifts from the mechanics of brushes, surfaces, and strokes to the virtual space I’m trying to evoke.

If I get too caught up in such superficial concerns late in the game, I’ve probably lost hold of the idea. Jotting down the initial idea in a quick sketch or even a couple of words can be a big help.

The most difficult part is the thinking stage, which is why I say: Painting is easy, thinking is hard.